The Habitation of Port Royal

Remarks

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture in Canada's Past in Pictures

For half a century or more after Cartier's voyages, France neglected the new world. Foreign wars and domestic strife between Catholic and Huguenots distracted the kingdom. Year after year the fleets of fishing vessels from the ports of France and Spain, Portugal and England visited the wild coasts of Newfoundland and the Gulf, but no attempt at colonization was made.

At length Henri IV won his way to the throne. and under his rule France, so long torn by religious and political conflict, found peace. The energies wasted in warfare turned toward industry and trade. Shrewd merchants and needy noblemen looked again to the new land. Numerous trading companies were formed, usually under some great nobleman's protection, which obtained a monopoly of the trade in furs, etc. on condition that a certain number of colonists should be sent out every year. All of these companies were eager to make large profits from their voyages, and they paid more attention to the trade in furs than to the settlement of the country. Some rough log buildings were put up here and there, as at Tadoussac, to store the furs and shelter the traders, a few of whom remained during the winter; but, for the most part, the merchants and their employees stayed only long enough to load their ships, and then sailed home again.

A real attempt at permanent settlement was made on the coasts of Acadia, the present-day Maritime Provinces. A nobleman, the Sieur de Monts, secured the right to trade, and formed a company which included merchants from several of the western and northern ports of France. In the early spring of 1604 he sailed with two ships from Havre for the new land. On board his vessels was a mixed company. There were hardy sailors accustomed to the western seas, criminals and vagabonds from the prisons, Catholic priests and Protestant ministers (for De Monts was a Huguenot), honest workmen, and volunteer settlers, some of them of good families and noble birth.

Among the company was Samuel de Champlain, a native of Brouage, on the Bay of Biscay. As a young man he had served in the religious wars. He had a love for the sea, he became a skilled navigator, and he had a thirst for exploration and adventure. He had made a voyage to the West Indies and Mexico, and on his return had published an account of what he had seen in these American colonies of Spain, then jealously guarded against foreigners and almost unknown. In 1603 he had joined a trading expedition to the St. Lawrence, which penetrated as far as the site of Cartier's Hochelaga, which was found deserted. When De Monts undertook his voyage next year Champlain, trained in surveying and map-making, accompanied him as geographer.

After exploring the coasts of present-day Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy, De Monts fixed upon an island at the mouth of the St. Croix River, on the boundary of Maine and New Brunswick, for the settlement. Houses were built, gardens were laid out, and here the colonists passed their first winter. It was a terrible winter. There was no good water on the island; there was not sufficient fuel; the cold was severe; huge masses of ice swept in the strong tides that cut them off from the mainland. Their food was largely salted meat, and scurvy raged among them, so that by spring thirty-five of their company of seventy-nine had died, and of the remainder one-half were helpless.

In June a vessel from France, commanded by Pontgrave, one of the partners, arrived with fresh stores, and De Monts set out to seek a more suitable place for his colony. For six weeks he explored the coasts of New England, but the Indians here had few furs to sell, and his settlement must depend largely on the fur trade in its early years. He therefore turned north again to be nearer his market, and, searching the shores of the Bay of Fundy, found the sheltered and spacious harbour now known as Annapolis Basin. Here, in August, 1605, De Monts brought the settlers of St. Croix island, transporting also some of the timbers of the houses. The place, which he named Port Royal, was situated on the north shore, opposite the Annapolis Royal of to-day. The forest was cleared, and before autumn the buildings were completed. De Monts sailed for France to seek further support for the colony, and some of the adventurers who had tasted enough of pioneer life returned with him. Champlain remained with the forty-three colonists who, under the command of Pontgrave, prepared to pass their second winter in Canada.

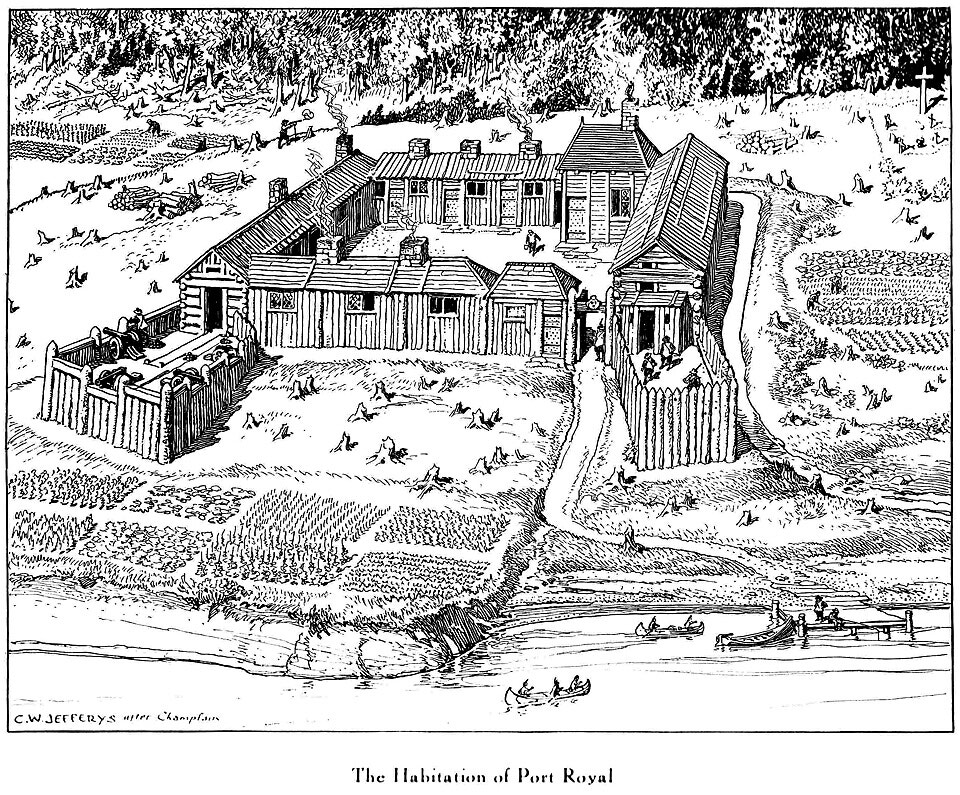

Champlain in his Voyages has told the story and given us drawings of these two settlements. The picture here shown is reconstructed from the engraving in his book, copied from his own drawing. The engraver knew nothing of the conditions of life in a new, rough country, and so gives us very few details of the construction of the buildings. The present drawing endeavours to show the materials of these earliest houses, and how they were built.

The settlement was surrounded by a palisade of tree trunks set upright in the ground. The houses, most of which were low one-story structures, probably were built in the same way, for where the soil was not too rocky and wood was plentiful this was the quickest way of putting up the walls of a house. That of the governor was made of boards, brought. already sawn, from France. This house is seen in the picture opposite the gateway. The roofs probably were of bark or roughly-hewn planks, the windows had no glass, but most likely were covered with parchment or oiled paper, and closed with inside shutters, the chimneys and fireplaces were made of field stones. Vegetable gardens were planted between the palisades and the bank of the shore, and the forest was roughly cleared away for some distance beyond the buildings. A few small cannon were mounted on an earthen embankment faced with heavy logs. A little stream led into a ditch alongside the eastern wall. Some of the settlers, all of whom were men, died, and a cross marks the locality of the burial ground.

These were the first houses to be erected as permanent dwellings by white men within the limits of what is now the Dominion of Canada, for the site of the St. Croix settlement is now within the boundaries of the United States and the few rough huts at Tadoussac were merely the temporary shelters of the fur-traders.

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture from The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Volume 1

The Habitation of Port Royal was the first permanent white settlement in America, north of the Spaniards. We have some scanty descriptions of it in the writings of Champlain and Lescarbot, and a few references in the Jesuit Relations, in addition to an engraving in Champlain's works, presumably from a drawing made by him. It was built by De Monts, from plans by Champlain, in 1605, and lasted until 1613, when it was looted and burned by Argall and an English force from Virginia. When the French re-occupied the territory they built the new Port Royal about seven miles farther up the Basin on the south side, at what is now Annapolis Royal.

In 1938 the Dominion Government through the Department of Mines and Resources, undertook its reconstruction on the original site. No pains were spared to make it as accurate as possible; information was sought from every available source in Canada , the United States and France, and the plans were prepared and the buildings erected under the careful supervision of Mr. K. D. Harris, the Departmental architect, with whom I worked as historical consultant. A happy feature of the undertaking was the collaboration of the "Associates of Port Royal," a group of Americans organized by Mrs. H. T. Richardson, of Boston, who had been interested in the project for several years.

The site was excavated with scientific accuracy by Mr. C. C. Pinckney, of Boston, and the work had the invaluable assistance of the knowledge and experience of Dr. C. T. Currelly, Director of The Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology. The foundation stones of the buildings were discovered, and it was seen that their positions agree with the descriptions and engravings in Champlain's works, and that they were grouped around a rectangular court of about sixty-four by fifty-two feet. A well was found in the middle of the courtyard, with many of its stones still in position. It was excavated to a depth of about eighteen feet , where a copious flow of water was reached. Every detail of construction was carefully worked out in accordance with the building methods and the style of the period. The massive chimneys were built of local stone, the fireplaces lined with bricks made from the near-by clay pits from which Poutrincourt made bricks over three hundred years ago. All the beams, planks, and shingles were hewn or sawn by hand, the nails and other iron work all hand wrought.

The drawing is copied from the architect's perspective view of the reconstructed buildings as they appear today, and should be compared with the engraving in Champlain's works.

Consult for full details of the reconstruction and data upon early building construction, articles by C. W. Jefferys in The Canadian Historical Review, December, 1939, and by Kenneth D. Harris in The Journal, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, July, 1940.

Publication References

-

Lescarbot, Marc. The Theatre of Neptune in New France…. Boston, Riverside Press, 1927. v.p. Illus.

-

Fortier, L.M. Champlain’s Order of Good Cheer, and some brief notes relating to its founder. Toronto, Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1928, 28 p. Illus.

-

Jefferys, Charles W. 1934 Canada's Past in Pictures, p.16

-

Bridle, Augustus. “Toronto ‘history-artist’ helps rebuild romance: C.W. Jeffreys [sic] adviser to experts restoring Old Fort Royal on Fundy Bay.” In Toronto Daily Star, Sept. 16, 1939, p. 15.

-

Jefferys, Charles W. “The reconstruction of the Port Royal Habitation of 1605-13.” In Canadian Historical Review, v. 20, no. 4, Dec. 1939, 368-377. Illus.

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1942 The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Volume 1, p.81

-

“The Order of Good Cheer: an organization that was part of the proud history of early Canada remains the symbol of Nova Scotia’s hospitality.” In Imperial Oil Review, Dec.-Jan. 1949-50, p. 25-29. Illus.

-

Kalman, Harold. A history of Canadian architecture, v. 1. Toronto, Oxford UP, 1994. 478 p. Illus.

-

Wasserman, Jerry, ed.. Spectacle of empire: Mark Lescarbot’s Theatre of Neptune in New France. 400th anniversary edition. Vancouver, Talon Books, 2006. 108 p. Illus.

-

LeBlanc, Ronnie-Gilles. The Habitation at Port-Royal, Acadia. 13 p. Illus. http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org Accessed November 22, 2014.

- Begbie Contest Society. “Canadian primary sources in the classroom: New France.” July 2017, 109 p. Illus. http://www.begbiecontestsociety.org/NewFrance.htm Accessed July 27, 2017.

Comments