The Battle of Batoche

Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1972-26-774

Remarks

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture from Canada's Past in Pictures

To most Canadians the outbreak of the North-West Rebellion in the early spring of 1885 came with the startling suddenness of an earthquake.

When Manitoba became a province, many of the Metis of the Red River valley, inheriting the roving and independent habits of their ancestors, the Indians and voyageurs of the old fur-trading companies, were unable to adjust themselves to the changing conditions brought about by the inrush of white settlers. Many trekked westward to the South Saskatchewan, where between Prince Albert and Saskatoon they planted a colony along the river banks. Here they lived in an isolated community of primitive farmers, hunters and fishermen.

But as the population of the West increased, the buffalo became exterminated, and soon the Metis, as well as the Indians, felt the loss of their main food supply. With the building of the railway came surveyors, land speculators, farming settlers. The Metis held no legal title to the lands on which they had squatted; their homes as well as their means of subsistence were imperilled. Some of them demanded treaty money on the strength of their Indian blood, some claimed that they were entitled to scrip for land. The government delayed decision, land patents were withheld, and protests and suggestions all seemed to fall upon deaf official ears. Meanwhile the surveyors ran their squared lines across the prairie, and settlers, traders, and speculators steadily trickled in.

In the summer of 1884, the Metis sent a delegation to Louis Riel in Montana, where he had been living for some years, after the Red River Rebellion of 1869, asking him to come back and help them to win their rights. He returned, and set himself to the work of agitation. By the spring of 1885 he had stirred himself and his followers to the pitch of armed rebellion. The neighbouring Indians, who had grievances of their own, naturally sympathized with their half-breed kinsfolk. Riel urged them to join in rising against the whites; but thanks to the influence of the Mounted Police, and the missionaries, the majority of the Indians took no part in the outbreak. Many of the more restless braves, however, in whose hearts still smouldered the old savage fire, took the warpath in defiance of the advice of their tribal leaders.

When the news came that blood had been shed by the Metis at Duck Lake on the 26th of March, and that Indian massacre had been committed at Frog Lake a few days later, the government and the public awoke to the seriousness of the situation. The militia was promptly called out. Men, arms, ammunition and supplies were rushed to the North-west. The C.P.R. tracks had been laid as far as the Rockies, with the exception of a few gaps along the north shore of Lake Superior. Across these the troops were transported in sleighs, or made their way on foot over the ice-bound lake or through the snow along the shore.

Three columns were directed toward the disturbed districts. The western one, under General Strange, marched to Edmonton, thence following the North Saskatchewan in quest of the rebellious Crees with Big Bear; the centre one led by Colonel Otter, pushed across country from Swift Current to relieve Battleford from the Crees under Poundmaker; while the eastern column, numbering about eight hundred and fifty, under General Middleton, the commander-in-chief, struck from Qu'Appelle toward the Metis headquarters at Batoche.

Middleton's column reached the South Saskatchewan and marched down its banks to Fish Creek. Here they encountered a party of Indians and Metis, under the command of Gabriel Dumont, an old buffalo hunter, the military leader of the rebels. After several hours of difficult fighting which cost the troops ten killed and forty wounded, the rebels retired.

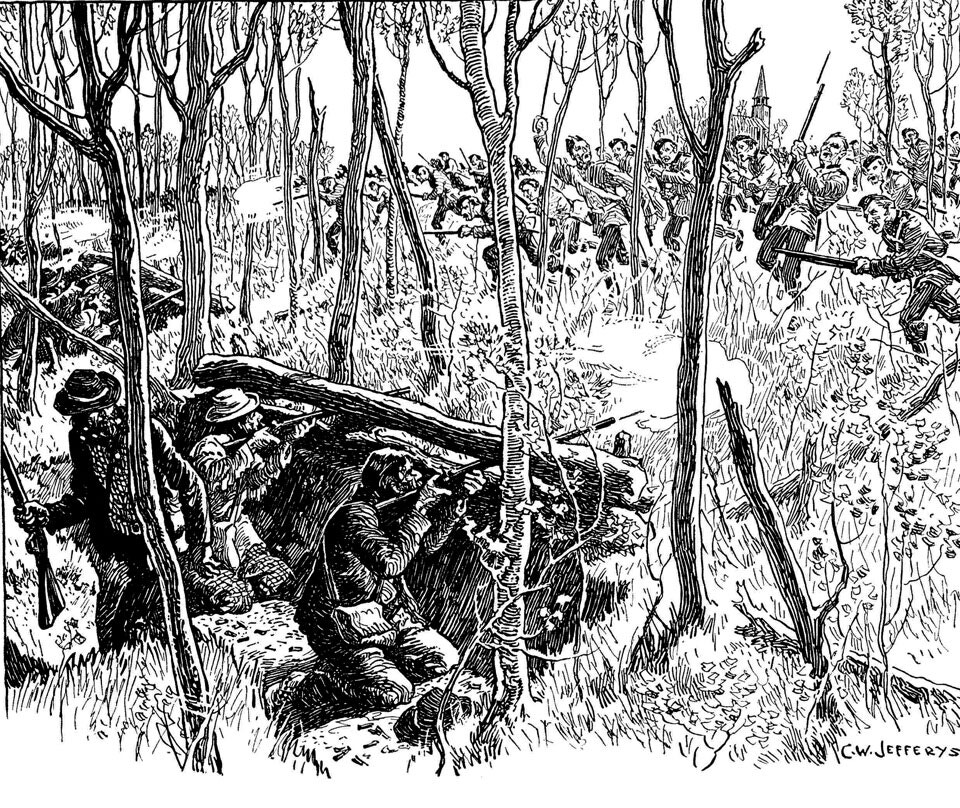

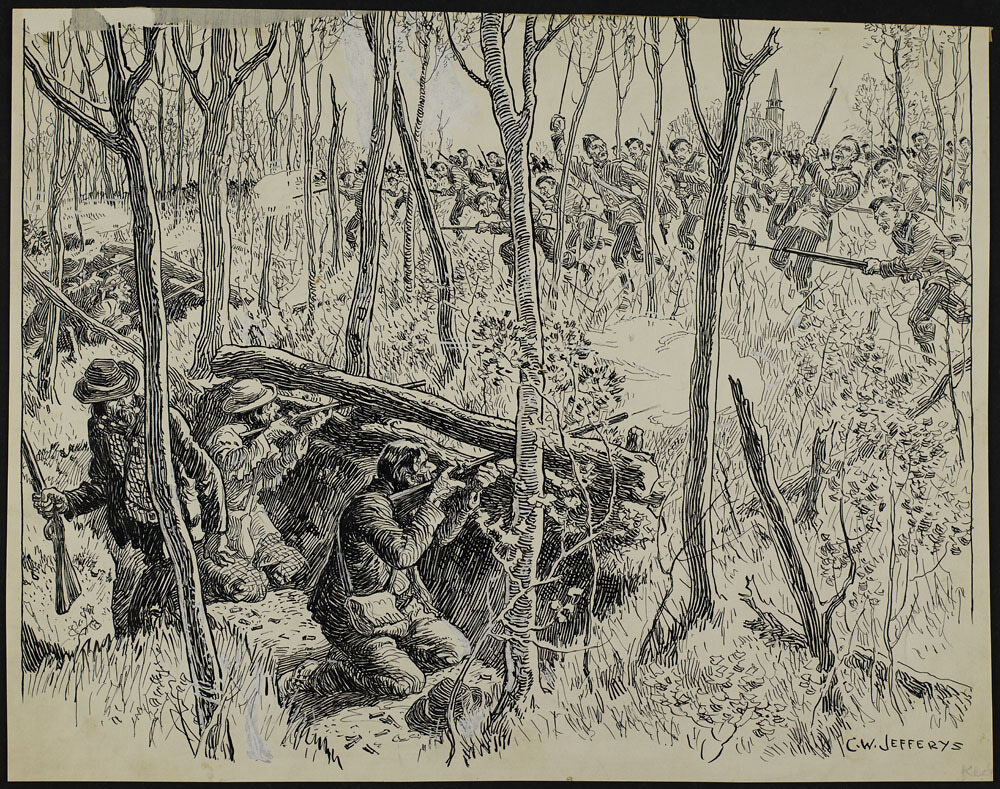

Middleton waited for reinforcements and supplies, and then pushed on towards Batoche, some miles down the river. On the 9th of May the column came within sight of the village. From the flat or slightly rolling open prairie, over which the troops advanced, a slope, covered with thick scrub and dense woods of poplar and willow, and cut up by coulees or ravines, led to a lower flat, on which stood the little village. All along the upper slope, just below its crest, screened by the thick bush, the Metis had dug rifle pits. About thirty of these pits can still be seen and show how cleverly Dumont made use of the natural features of the ground.

Most of the rebels were expert marksmen, and all knew how to take advantage of every bit of protecting cover; but many of their weapons were muzzle-loading muskets, and their ammunition was too scanty for a prolonged siege. The majority of the troops were men called from offices, ships and factories. Several companies of scouts, mounted and on foot, made up for the deficiencies of the militia in local knowledge and experience, and were of invaluable service, while artillery, and a Gatling gun, an early form of machine gun, a new American invention, gave the government forces the advantage of a heavier fire.

A stern-wheel steamer, the Northcote, accompanied the troops downstream. Protected by bags of oats, planks, and boxes of tinned provisions, and manned by a company of infantry regulars, she was to attack the flank of the rebel position. But the Metis fire riddled the wheelhouse, and drove the steersmen to shelter, the wire cable of the ferry stretched across the river tore down the smokestack, and the steamer drifted helpless out of the fight below the village.

Meanwhile the troops advanced to the edge of the slope. Here they were held by the heavy fire of the hidden enemy, and though the artillery and the Gatling were brought up, it was impossible to make further advance without serious loss of life. Middleton withdrew the troops from their exposed position and sheltered them in a hastily entrenched camp for the night. The next day and the next were repetitions of the same skirmishing attacks, which gained little ground, but gave the raw soldiers confidence, and practice in keeping themselves under cover.

On the fourth day, Tuesday, the 12th of May the General decided to attack the Metis vigorously and capture the position. His plan was to attack, with all his mounted men. one gun and the Gatling, about a mile north-east of the village and thus draw the Metis to defend that part of their line. Meanwhile the infantry were to take up their old positions, and when the sound of firing was heard from the direction of the General's attack, they were to press forward in full strength. Middleton set off across the prairie and opened fire. A strong wind was blowing from the south-west, and little firing was heard by the expectant infantry, and they were not ordered to advance. Middleton waited, but seeing no sign of their movements, returned with his force at noon,"much annoyed." as he says, that his orders had not been obeyed.

After dinner the infantry took up their old positions in the firing line. Officers and men were now weary of the tedious daily skirmishing and impatient to come to closer action. They pressed forward into the bush, and cheering, rushed the rifle pits. The guns opened fire upon the village, and the whole force rapidly advanced. The Metis were put to flight and the village was occupied. The backbone of the Rebellion was broken.

Dumont escaped to Montana, whence he returned years later to spend his last days peacefully among his own people. Riel was captured three days after the battle, tried at Regina, and on November 16th, executed. Eight Indians found guilty of murder were hanged at Battleford. Poundmaker surrendered as did Big Bear, after a harassing pursuit of many weeks. They, and a number of Metis were sentenced to imprisonment, but all were released before their full terms were served.

Batoche to-day is but a name: of the Metis village only the church, the priest's house still showing an attic window with a bullet hole through it, and one other building, remain. In the little graveyard a small monument bears the names of the brave, misguided Metis and Indians who fell in the last armed conflict in which Canadians faced each other, and who now lie beneath a group of grey, lichen-covered wooden crosses near by.

Publication References

-

Imperial Life Assurance Co. of Canada. A few facts. Toronto, Imperial Life, [1913]. [32 p.] Illus., Fact 27 - “The Battle of Batoche, 1885”

-

Howay, F. W. Builders of the West: A Book of Heroes. Toronto, Ryerson, 1927. 251 p. Illus. p. 44 - “The Battle of Batoche”

- Kennedy, Howard Angus. The North-West rebellion. Toronto, Ryerson,1929. 32 p. Illus. p. 3 - “The Battle of Batoche”

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1930 Dramatic Episodes in Canada's Story, p.75

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1934 Canada's Past in Pictures, p.130

-

Jefferys, Charles W. “Fifty years ago: scenes of the Rebellion of 1885 revived in sketch and story by Canada’s noted historic artist.” In Canadian Geographic Journal, June 1935, p. 258-269. Illus. p. 258 - “The Battle of Batoche”

-

Plummer, Kevin. “Sketching cultural nationalism.” July 18, 2009. 7 p. Illus. http://torontoist.com/2009/07/historicist_sketching_cultural_nationalism.php

Comments