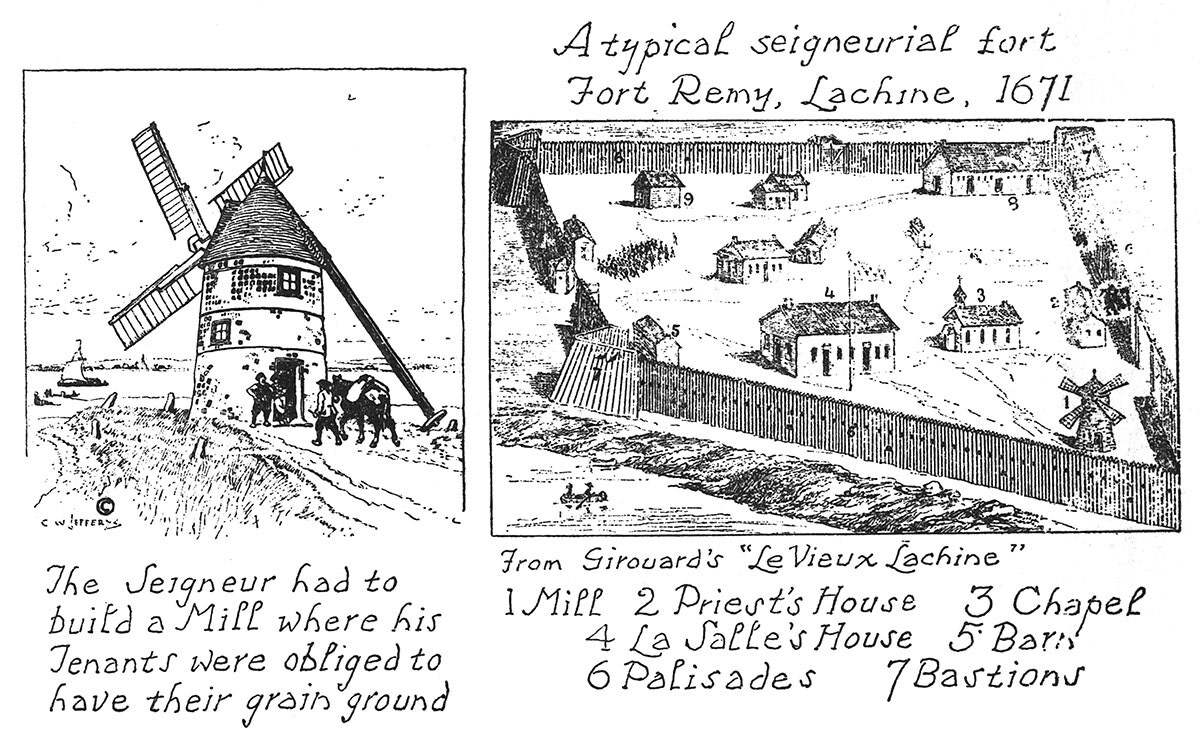

Seigneurial Mill. Seigneurial Fort

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1972-26-484

Remarks

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture from The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Volume 1

Among the first needs of a settlement was a mill for sawing logs, and another for grinding grain. Both sawmills and grist mills were built on the streams and run by a water-wheel. For grinding grain, windmills were used also. These were built along the shore of the St. Lawrence and the other broad rivers where their sails could get the full sweep of the breezes.

Several of these early windmills are standing today, though no longer in use. They are built of roughly dressed stone, heavily mortared, with walls two or three feet thick. They are circular in form, and three storeys high, surmounted by a high conical wooden attic or top storey, which can be turned round on a cog-wheel built on the top of the wall, so that the wings can be set to catch the wind from any quarter. On the opposite side to the wings a long beam slopes from the roof to the ground, where a small wheel is attached to it. This beam is pushed around until the right position is reached, when the wings, over which canvas sails are stretched, begin to revolve.

Early forts, whether on the frontier or in the more settled seigneuries, were generally built of logs set upright into the ground side by side to form a palisade. The logs usually were sunk about three feet into the earth, and extended fifteen or sixteen feet above the ground. Their tops were pointed, and along the inside of the palisade was built a platform on which the defenders could stand to fire over the top, or through loop-holes cut high enough to make it impossible for the attackers to put their own guns through them and thus shoot those inside. In most cases at the angles of the fort were placed blockhouses, built of heavy logs laid horizontally. These corner blockhouses, called bastions, projected beyond the palisades and were pierced by loop-holes through which the defenders could fire along the outside line of the connecting palisade, which was called the curtain. Sometimes a blockhouse was built over the entrance gateway, and a few small cannon were mounted there and in the bastions.

The more important forts were surrounded by a ditch, and the earth dug out was thrown up on the inner side to make an embankment in which the palisades were set. Over the ditch or moat, at the entrance, was a hinged bridge, which could be drawn up by ropes or chains to close the gateway in times of danger.

Published References

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1942 The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Volume 1, p.148

Comments