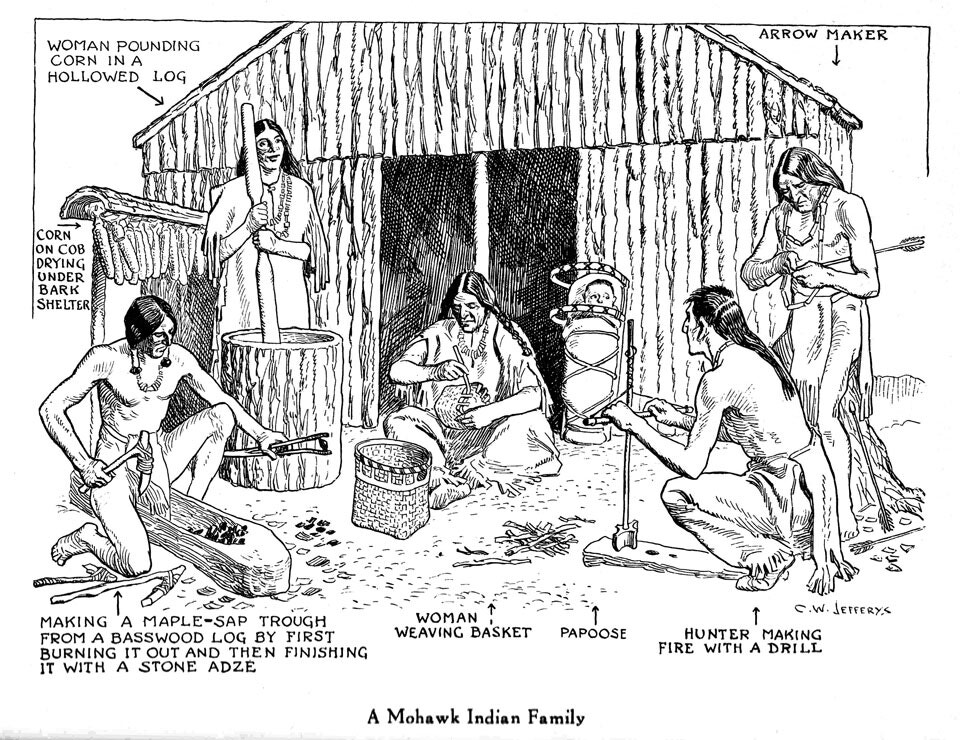

Mohawk Indians in Front of an Elm Bark lodge

Also Named: "A Mohawk Indian Family"

Illustration from Pen & Ink

Remarks

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture in Canada's Past in Pictures

Woman pounding corn in a hollowed log.

Corn on cob drying under bark shelter.

Arrow maker.

Making a maple sap trough from a basswood log by first burning it out and then finishing it with a stone adze.

Woman weaving a basket.

Papoose.

Hunter making fire with a drill.

A Mohawk Indian Family

The Indian Tribes connected with the history of Canada may be grouped into four divisions: Algonquins, Athapascans, Pacific Coast Indians, and Huron-Iroquois.

The Algonquins were widely spread from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains. The Northern and Eastern tribes were mainly woodland hunters and fishermen; much of their travel was by waterways, for which they used the birch bark canoe, one of their most noteworthy inventions. The Western tribes of the open plains lived on the buffalo, whose flesh and hides provided them with food, shelter and clothing. They possessed no horses until the middle of the 18th century. The Algonquin tribes, living by the chase, had no permanent, villages or settled habitations. Their tents, or "teepees," were covered with birch bark, in the northern woods, and with buffalo hides on the prairies.

The Athapascans occupied the North-West, from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountains and the valley of the Fraser River. They lived by hunting and fishing and had no permanent homes. They travelled on snowshoes in the winter, as did all the northern tribes. Deep and soft snow required a different kind of snowshoe from that used on hard, wind-driven snow, or on snow with a slippery crust. The canoe and the snowshoe are the most remarkable examples of Indian skill in handicraft.

The West Coast Indians belong to entirely different families from those of the rest of Canada. They were unknown to the whites until the 18th century, when Russians, Spaniards and Englishmen explored the North Pacific.

The Iroquois and Hurons occupied the country south of the Algonquins. Before the white man came, a branch of the family, the Hurons, had split off, and between them and the Iroquois a deadly enmity existed during the early period of Canadian history. The Hurons occupied the district around Georgian Bay. The Iroquois proper lived south of Lake Ontario, between the Hudson and the Niagara Rivers, in a Confederacy of Five Nations- Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas. Later another tribe joined them -- the Tuscaroras -- and many of the descendants of these Six Nations to-day are settled on the Indian reserve on the Grand River near Brantford, and at Deseronto, Ont., while others live at St. Regis and Caughnawaga, Que.

In many respects the Iroquois show the highest development of the Indians of North America. They were a people of settled habitations; they built long houses of logs and bark, large enough to shelter several families, and they lived in villages, surrounded by palisades for defence. They did not live entirely by hunting and fishing, but tilled the soil and grew corn, pumpkins, beans and tobacco, and stored provisions for common use. Their tools and weapons were of bone, wood, flint or other stone, and they made rude knives beaten out of sheet copper procured in trade from the Indians of the Lake Superior regions. With such implements they made canoes out of logs charred and roughly hewn, or of elm bark, sewn together with tough root fibres and sealed with spruce gum. Neither of these was equal to the canoe made of birch-bark, which was lighter, more durable and speedier. White birch trees, however, were less plentiful in the country of the Five Nations than in the more northerly regions of the Algonquins and Hurons. Consequently the Iroquois were compelled to use these clumsier materials, or to rely upon the lighter canoes captured from their foes, or the bark gathered in their hunting trips or their raids into the country of their northern enemies. Besides baskets woven of the inner bark of the elm, they made a crude pottery of clay, baked by fire or sun, in which they seethed their food. Their clothing was made of dressed deer hide, with the addition in winter of fur garments or robes of bear, beaver and other skins.

The picture is drawn from a model in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, illustrating the occupations of a Mohawk family before the coming of the white man.

Publication References

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1934 Canada's Past in Pictures , P.7

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1942 The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Vol. 1 , p.48

-

Long, Morden H. A History of the Canadian People: vol. 1, New France. (Toronto: Ryerson, 1942). 376 p. Illus. [note: only vol. 1 was published]

p. 37 - “A Mohawk Indian family in front of their elm bark lodge. From a group in the Royal Ontario Museum” [a dioarama that he did?] -

Walker, Paul. C.W. Jefferys and images of Canadian identity in school textbooks. Kingston, Ont., Queen’s University, 1990. Masters of Art thesis. 130 p. Illus. p. 60 - “Figure 1. A Mohawk Indian Family”

-

Dawendine. Iroquois fires: the Six Nations lyrics and lore of Dawendine. Ottawa, Penumbra Press, 1995. 158 p. Illus. p. 102 - “Mohawk Indians in front of an elm bark lodge”

Comments