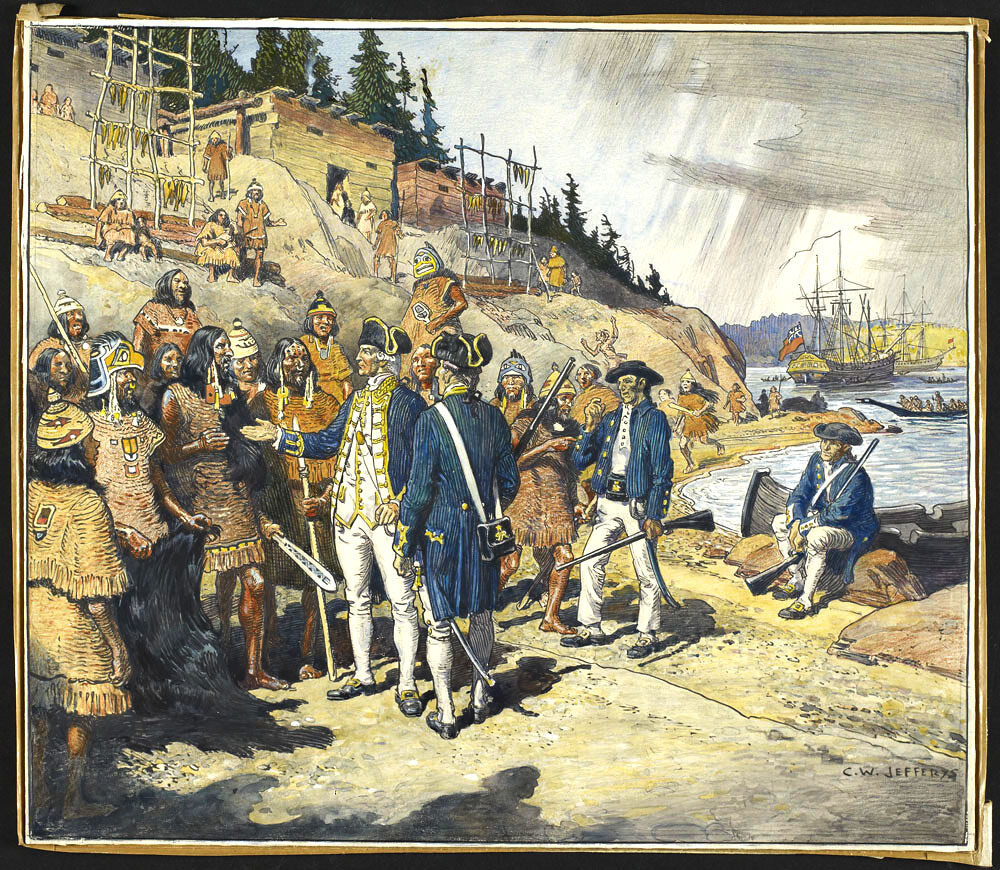

Captain Cook at Nootka

Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1972-26-765

Remarks

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture from Canada's Past in Pictures

For centuries explorers searched for a break in the land barrier of America that would give a north-west passage for vessels to Asia, and make unnecessary the long voyage around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. Drake in 1579 had sought for a channel that might lead him home from his raid up the western coast of America. In the 18th century the Russians from Asia and the Spaniards from Mexico and California sent expeditions in search of a legendary strait.

In 1776, while discontent in the colonies on the Atlantic coast was breaking out into rebellion and a declaration of independence, the British Government fitted out two ships for a voyage of discovery in the Pacific, with orders to return along the northern coast of America, if a possible route in that direction could be found. The command was given to Captain James Cook.

Cook was the son of a Yorkshire farm labourer. He was born with a taste for the sea, and became a sailor in the merchant service, in which he spent several years. When war broke out in 1755 he joined the Royal Navy at the age of twenty-seven, soon attracting the attention of his superior officers by his ability and strict attention to his duties. He served in the fleet which carried Wolfe's army to Quebec, and during the siege Cook was employed in taking soundings and making charts of the St. Lawrence. In 1760 Cook received a commission and for some years thereafter was employed on the coasts of the Gulf and the North Atlantic. Always eager to learn, and endowed with mental powers of a high order, he gained the reputation of being one of the most capable navigators in the service. In 1768 Cook was appointed commander of a scientific expedition to the South Seas. So successful was this voyage that he was given charge of a second expedition which from 1712 to 1775 explored the Southern Hemisphere.

When the Government projected a further voyage of discovery in the Pacific and in search of a north-west passage, Captain Cook was regarded as the officer best qualified to conduct the expedition, and to him accordingly was given the command. He sailed from the English Channel with his two ships, the Resolution and the Discovery, in July, 1776. After visiting New Zealand and many of the islands of the Pacific, he proceeded toward the north-west coast of America.

Early in March, 1778, he came in sight of the land. Boisterous gales drove the ships off the coast for several days, but sailing northward he reached Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. Here Cook remained for almost all the month of April, repairing his vessels, the masts and rigging of which were badly damaged, and laying in supplies of wood and water. Having put his ships into good condition, he resumed his voyage, still sailing northward along the coast of Alaska, which he examined carefully in the hope of finding a passage that might lead to the east. He passed through Bering Strait until he found his progress barred by solid ice. It was now nearing the end of August, too late in the season to attempt to return by a northern passage, if one existed. Cook, therefore, decided to turn back to the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawaii), and spend the winter exploring the Pacific in that neighbourhood until the next summer, when he would make another attempt to find a passage, though from his observations he had little hope of succeeding. He did not live to try the search again. Disputes arose with the Hawaiian natives, and in an encounter with them Cook was killed. After his death Captain Clerke, who succeeded to the command, made a final effort to the north-eastward, but ice again stopped progress. Clerke died, and the two ships, under the command of Captain Gore, returned to England by way of Asia and the Cape of Good Hope in October, 1780.

Expeditions of scientific discovery such as this usually included in the party a draftsman who made pictorial records of the places and peoples visited. On Cook's last voyage he was accompanied by a young artist named John Webber, born in London of Swiss parentage. Webber made numerous sketches during the voyage, he was present at Cook's death, of which he later made a drawing, and on his return to England was engaged for some years in preparing the finished drawings and supervising the engravings from them, which were published in the account of the expedition. He was elected a member of the Royal Academy, and won a considerable reputation as a landscape painter. Both he and Cook were keen and accurate observers. Webber's drawings give valuable details of the physical character of the natives, their costumes, implements and dwellings, and of the scenery of the countries explored. On these drawings and on Cook's admirably graphic written descriptions, the accompanying illustration is based.

Cook tells us that the Indians of Nootka were in general below the average height, with plump figures, round broad faces, high cheekbones, flat noses and wide nostrils, thick lips, abundant coarse black hair and sometimes thin straggling beards. They were clothed in garments made of tree-bark, beaten into fibres which were knotted and plaited together to form a rough fabric, and edged with a narrow strip of fur. Sometimes a fur skin was worn over the bark garments. Their ears and noses were decorated with shells, bones, rings or pieces of brass and copper. Some, especially the women, wore conical hats made of woven straw, and these, as well as their bark clothing, were ornamented with painted designs.

Their weapons were bows and arrows, slings, clubs of bone, stone tomahawks, and spears, tipped with bone or flint, or, in a few cases, copper or iron. They travelled in canoes, many of them forty feet or more in length, dug out of tree trunks, with large projecting prows carved and painted to represent animal figures.

Their houses were about seven or eight feet high, built of planks roughly hewn, with holes cut out for windows, and the roof planks laid loosely so that they could be moved to give light and air. Mats of coarse bark fibre or straw, and well-made wooden boxes for seats and storage purposes, were their furnishings. Inside and outside, thin poles were set up on which fish were suspended to dry in the sun or in the smoke of their fires.

At the end of the single-roomed houses farthest from the door were placed large tree trunks, carved into the shapes of men, beasts or birds and painted in strong vivid colours. These images, commonly known to-day as totem poles, apparently in Cook's time were to be found only inside the houses. None of Webber's drawings show any totem poles outside in front of the houses.

It must have been a difficult task to carve these figures and to hew their house planks and their canoes with the rude implements of stone or bone which were their only tools before the white man brought them metals. Cook found that some of them had pieces of iron, brass and copper, sometimes fixed to handles like chisels, which doubtless they had procured in trade with other Indians in contact with white men, or from Spanish and Russian ships. He says that the natives were eager to get metal of any kind for which they traded the most valuable furs: and a brisk and profitable trade sprang up between them and the sailors who loaded themselves with skins of the seal and sea-otter which they afterwards sold for high prices in China on their way home. By the time the ships left Nootka hardly a bit of metal was left aboard except what belonged to their instruments, and the brass buttons had been stripped from many suits, so that the sailors had to tie their garments together with bits of string.

Cook speaks of the excellence of their decorative designs, and of their skill in handicrafts, of which their thievish abilities were perhaps a perversion. With metal tools in their capable hands, they were able to produce more rapidly work of a greater degree of finish. Most of the large totem poles in our museums no doubt date from this time, and the arts and crafts of the West coast probably reached their highest development during the period when the white traders flocked to the North Pacific in search of furs.

C.W. Jefferys' notes about this picture in The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Vol 2

In the narrative of Captain Cook's last voyage will be found detailed descriptions of the West Coast Indians, their houses, clothing, tools, etc., as they were in 1778. Also included are several engravings from drawings made by John Webber, R.A., the official artist attached to the expedition.

Cook says that the houses of the Nootka Indians were about seven or eight feet high, the back part higher than the front, made of hewn planks, with the sloping roof boards laid loosely so as to be removable for light, air and the escape of smoke. At the end farthest from the door were placed large tree trunks, carved into shapes of men, beasts and birds, and painted in vivid colours. None of Webber's drawings show these so-called totem poles outside the houses. The only tools for wood working possessed by the natives before the white men came were implements of bone and stone for carving, and coarse-scaled fish skins for polishing. Cook found that some of them had pieces of iron, brass and copper, which were fixed to handles to form chisels or gouges. These metals had been procured in trade from Indians in contact with the whites, or from Spanish and Russian ships. With the possession of steel tools obtained from the trading vessels which frequented the coast after Cook's explorations, the native art of carving rapidly developed to a high degree of finish. Totem poles became taller and more elaborately carved, and were now placed outside the houses. These exterior poles therefore date only from the time of the white men's arrival, and most of those now surviving are probably much later. Several specimens are to be seen in Canadian museums.

Mention is also made of frames of thin poles on which were hung fish to dry in the sun outside the houses, as shown in the drawing, which is based on Webber's picture of the Nootka village.

Cook describes the clothing of the Coast Indians as being made of pine bark fibres plaited together and of wool which "seems to be taken from different animals." Over these garments was frequently thrown the skin of a bear, wolf, or sea otter. Sometimes they wore carved wooden masks or visors, applied on the face, or to the upper part of the head. Some resembled human faces, others the heads of birds and of sea and land animals. Hats made of fine matting were also worn.

He remarks on the eagerness of the natives to obtain metal, stealing it in addition to getting all they could by trading. Brass, in particular, was sought after so keenly that hardly a bit of it was left in the ships except what belonged to their necessary instruments. Whole suits of clothing were stripped of every button, and copper kettles, candlesticks and canisters all went to wreck. In exchange the natives gave the valuable skins of the sea otter. In the drawing one of the Indians is shown trying to induce a sailor to part with his sleeve buttons.

Publication References

-

Howay, F. W. Builders of the West: A Book of Heroes. Toronto, Ryerson,1927 251 p. illus.

-

Burkholder, Mabel. Captain Cook. Toronto, Ryerson Press, 1928. 32 p. Illus.

-

Moore, Kathleen and McEwen, Jessie. A Picture History of Canada. Toronto, Thomas Nelson, 1930? 103 p. Illus.

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1930 Dramatic Episodes in Canada's Story, p.59

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1934 Canada's Past in Pictures , p. 86

- Jefferys, Charles W. 1942 The Picture Gallery of Canadian History Vol 2. p.16

-

McEwen, Jessie and Moore, Kathleen. A Picture History of Canada. Toronto Nelson, 1966. Rev. and enl. Ed. 137 p. Illus.

- Gibson, Nancy 1990 C.W.Jefferys: The Artist as Historian

Comments